|

Anxiety disorders, which include everything from generalized anxiety, to social phobia (aka, social anxiety), to obsessive-compulsive disorders, are the most commonly diagnosed mental health problem in the US. In fact, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million US adults. More disheartening is that less than half of those with anxiety disorders receive help for their struggles. When I work with clients who have anxiety, I often discuss with them the cycling and self-reinforcing patterns that anxiety tends to induce. This three-part series will review common ways that we give in to, and therefore worsen, our anxiety. Part 3: Self-Medicate It Anxiety can be exhausting, grueling, and overwhelming. It consumes copious amounts of physical energy and mental space. Many clients describe their racing thoughts as a track running constantly in their minds at 100 miles per hour, taking up valuable room that could be used for more productive things. In Part 1, we discussed what anxiety is and the value of insight. In Part 2, we reviewed the negative effects of finding ways to avoid anxiety triggers, which only serves to make anxiety worse in the long-run. However, avoidance is only one of many less-than-helpful ways of coping with anxiety. The discomfort of anxiety offers tempting invitations to find quick fixes for relief. Those facing physical exhaustion from anxiety-induced sleep issues or fatigue may grab a few extra cups of coffee or a Red Bull to get through the day. Some who always feel keyed up or tense may look to alcohol or other drugs to take the edge off. Still others turn to what they can control and rely on - food, shopping, social media - to provide distraction or comfort. Let's break down some of these quick-fix anxiety responses that may not be so helpful for long-term symptom reduction:

Something to try: A saying I use often with clients is to strive to find your comfort within life's discomfort. We have no way to ensure life will be smooth and easy; in fact, it tends to be just the opposite - but that's what makes our lives meaningful. We are tasked with finding ways to cultivate a sense of peace even when our lives feel far from peaceful. When you are feeling anxious, practice closing your eyes, taking some measured breaths, and mentally stepping back so you can appraise your situation from a different perspective. Try to hold in your mind the realities of whatever discomfort is causing your distress, but also hold your grit - your inner strength and resilience - and remind yourself that you can lean into the discomfort with grace and persevere. Breathe through the discomfort and notice how even in the midst of our tumultuous worlds, we can still hold peace within. I hope you enjoyed this three-part series on anxiety! Are there other topics you'd like to learn more about? Share them below or reach out.

0 Comments

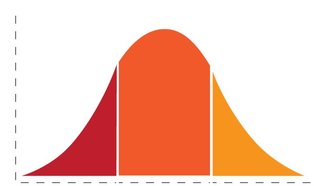

Anxiety disorders, which include everything from generalized anxiety, to social phobia (aka, social anxiety), to obsessive-compulsive disorders, are the most commonly diagnosed mental health problem in the US. In fact, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million US adults. More disheartening is that less than half of those with anxiety disorders receive help for their struggles. When I work with clients who have anxiety, I often discuss with them the cycling and self-reinforcing patterns that anxiety tends to induce. This three-part series will review common ways that we give in to, and therefore worsen, our anxiety Part 2: Give Into It By far the most common anxiety mistake I see people making is giving into it. As I reviewed in Part 1, anxiety often boils down to a misapplied fight-or-flight response to a threat that isn't truly life-or-death. It is a good thing that we have fight-or-flight, as it keeps us from harm through readying our minds and bodies for action or escape. However, sometimes that response can get linked up with things we face in life that are not actually threatening enough to warrant such a strong neurobiological response (e.g., meeting new people, public speaking, spiders, unknowns, compulsive behaviors, being imperfect, etc.), resulting in a state of anxiety. When we are in an anxious state, our minds and bodies are basically screaming at us to get ourselves OUT of that situation through trying to find things to control (hello, perfectionism!), numb the anxious feeling (hey there, comfort food), or avoid the threat altogether. This post focuses on the danger of avoiding the anxious trigger. What happens when we listen to our screaming brain and simply avoid the trigger? Avoidance often gives us immediate relief from anxiety, but it does us no favors in terms of making our anxiety better. In fact, it seems to make it worse. By giving in and avoiding the trigger, we reinforce our brains, telling ourselves that yes, this threat I am facing truly is life-or-death, and we give our fight-or-flight response a pat on the head (brain?) for a job well done. The next time we face the same trigger, our brains will respond as actively, if not even more so, as the first time we faced it because we reinforced the fear by giving in. So what should we do instead? Face the fear directly. Anxiety lives on a bell curve (see below) - it builds up with those initial signs (the red zone) and continues to grow in intensity (the orange). Often, we look for ways to cut those anxious feelings before it crests - we become afraid of our own anxiety - through avoidance, numbing, or control. However, if we can muster our inner strength to sit in the discomfort of anxiety, it will subside. The acute anxiety state does not last forever, and the more that we face the threat, breathe, and ride the wave, the less intense our response will get every time we face our fear. I experienced success with facing fear head on when it came to public speaking. Back in high school and college, I would be an absolute mess when I had to present a speech in front of my class. Shaking hands, quivering voice, cold sweat, that gripping, hollow feeling in my stomach like when you miss the last step on a staircase - all that good stuff. However, I kept pushing myself to face, acknowledge, and ride out those anxious feelings every single time. Over the years my discomfort became more manageable, and I have since completed some pretty big milestones, including conference presentations, my dissertation defense, and currently teaching graduate students for the sixth semester in a row. I still get butterflies, but my fight-or-flight response is far more subdued and manageable - and I fully attribute it to facing my public speaking fear and telling my brain over and over, "This makes me feel some stress, but I know I will be okay. Let's channel these nerves into excitement and get on with it."

Something to Practice: Identify a trigger for your anxiety response. Sticking with my anecdote above, we will use public speaking for an example.Then, think about a step towards conquering that fear. The first step should be anxiety-provoking enough -- but not overwhelmingly so. For example, one step towards conquering public speaking fear might be raising your hand in class. Then, schedule 3-5 times this week to practice facing that initial step without avoiding it. Keep track of your anxiety symptoms before, during, and after - and notice how they will decrease in intensity with repeated exposure. Once you get to the point where raising your hand no longer elicits substantial anxiety, move to the next step, such as attending a networking event or job fair, or taking a lead role for a class presentation. Work your way systematically through these steps and watch the anxiety drop. Extra resources: More about fear exposure for social anxiety Treating phobias with fear hierarchies More on anxiety and fight-or-flight Have you been able to conquer any of your fears? Share your success stories in the comments! Anxiety disorders, which include everything from generalized anxiety, to social phobia (aka, social anxiety), to obsessive-compulsive disorders, are the most commonly diagnosed mental health problem in the US. In fact, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million US adults. More disheartening is that less than half of those with anxiety disorders receive help for their struggles. When I work with clients who have anxiety, I often discuss with them the cycling and self-reinforcing patterns that anxiety tends to induce. This three-part series will review common ways that we give in to, and therefore worsen, our anxiety. Part 1: Ignore It Ignorance is definitely not bliss when it comes to understanding what your mind and body are doing when you feel anxious. I think about anxiety (vs. appropriate fear) as an incredibly valuable neural response that is being either overblown or misapplied. In other words, the sensations that accompany an anxious state (accelerated breathing and heart rate, sweaty palms, muscle tension, decreased or increased appetite, racing thoughts, adrenaline rush) are highly useful when we are faced with actual threats to our safety or well-being. These bodily and cognitive changes represent our fight-or-flight response that readies us for survival in threatening situations. Our bodies are poised for action with activated muscles and quick respiration and heart rate, and our thoughts are running on high speed to alert us to our surroundings and possible ways to escape. Think about how adaptive this response is, especially remembering what life was like for the original humans fending off vicious predators and fighting for the survival of our species.

However, anxiety happens when that fight-or-flight response is misapplied to situations that aren't actually threatening to our safety, or at least not threatening enough to truly need that type of response. This is where having insight into what is happening mentally and physically can give you some leverage with anxiety - it gives answers to what you are feeling, it fights "anxiety about anxiety" (e.g., thinking you may pass out or die due to how your body feels in a state of fight-or-flight), and it opens up the possibility for challenging your anxious thoughts and practicing physical relaxation training to regain a sense of calm. Truly, knowledge is power when it comes to managing anxiety. Something to practice: If you are feeling anxious or even just stressed out, try to pause for a minute and notice what is going on in your body and mind:

Keep an eye out for Part 2, which will discuss how giving in to our fears exacerbates anxiety. What strategies do you use to manage stress and anxiety? Share your go-to coping methods in the comments below. When it comes to figuring out the type of therapy best suited for your needs, you may find yourself in murky waters when trying to decipher different therapeutic styles. Each post in this series serves as a primer on a major therapeutic approach to guide you in the right direction. It is important to note that many clinicians identify as integrative rather than adhering to a single school of thought, though there are some that stick to one orientation over others. Even within one school of thought, however, the individual therapist inevitably brings their own unique style to the work, so nothing here is cut and dry. Additionally, on the whole, research has shown support for success with all major schools of thought! So even if you feel unsure about what style is suited for you, with a good therapy relationship you should be positioned for success. Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is a specialized type of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) that maintains a focus on interpersonal dynamics and relational distress. It was created in the 1980s by psychologist Marsha Linehan as a specialized treatment for those grappling with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). Growing up, Linehan was given a range of inaccurate psychiatric diagnoses and extreme forms of "treatment" to try to cure what she now believes was BPD. BPD only became an official diagnosis in 1980, though references to it in psychological literature are present decades prior. Linehan's own struggles with mental illness and eventual success in managing her mental state to become a thriving and high-functioning professor of psychology served as her inspiration for developing the DBT approach.

DBT is a great treatment approach for those who have intense reactions to emotional situations, especially situations related to interpersonal relationships. For some, changes in relationships, whether it be movement towards OR away from intimacy with another, can elicit very strong and overwhelming emotional responses. DBT is especially designed to aid in managing strong emotional reactions through building skills for mood regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness (e.g., meditation, staying present), and strategies to improve interpersonal effectiveness and relationships. It is designed to help people find balance between dialectics (e.g., opposites), and practice sitting in grey areas rather than black-and-white thinking (e.g., recognizing and tolerating ebbs and flows in relationships vs. believing that getting in an argument with a partner means the relationship is doomed). DBT capitalizes on the individual's strengths to aid in symptom reduction and progress. It utilizes similar components of CBT, with an effort towards identifying and challenging unhelpful thinking patterns, as well as relaxation training and mindfulness practices to re-learn how it feels to be at peace. DBT sessions are typically structured, time-limited, and present-focused. It is administered in individual, group, or a combination of group and individual modalities. While it was developed originally for and remains the top choice treatment for BPD, it has also been successful in treating post-traumatic stress disorder, some eating disorders, depression, and substance abuse. Interested in finding a DBT therapist for yourself? Check this post for ways to get connected with a therapist. Some other helpful resources on DBT: Overview and Applications of DBT Therapy DBT Skills and Worksheets DBT Skills Workbook When it comes to figuring out the type of therapy best suited for your needs, you may find yourself in murky waters when trying to decipher different therapeutic styles. Each post in this series serves as a primer on a major therapeutic approach to guide you in the right direction. It is important to note that many clinicians identify as integrative rather than adhering to a single school of thought, though there are some that stick to one orientation over others. Even within one school of thought, however, the individual therapist inevitably brings their own unique style to the work, so nothing here is cut and dry. Additionally, on the whole, research has shown support for success with all major schools of thought! So even if you feel unsure about what style is suited for you, with a good therapy relationship you should be positioned for success. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a widely utilized therapeutic orientation and has grown tremendously over the last few decades. Aaron Beck, MD is considered the father of modern CBT and its structured, scientific, and organized approach to problem-solving. CBT involves an emphasis on education to improve self-awareness and develop coping strategies for achieving behavioral change and more positive feelings. CBT tends to focus not on HOW your struggles came to be, but more exclusively on understanding how these struggles manifest and what you can do to change -- it is heavily goal-oriented. Many clinicians integrate CBT with other therapeutic approaches, as it is a great framework for short-term symptom reduction within the context of a deeper insight-oriented therapy.

CBT techniques focus on the links among thoughts, feelings, and behavior; at its core, CBT hones in on irrational, negative, and distorted thinking patterns (see: "thinking traps"), which connect to low mood and unhelpful behavioral patterns. The therapist first works with the client to identify unhelpful thinking patterns that support low mood and maladaptive behaviors. Next, the clinician provides a model of ways to effectively challenge and alter those cognitive patterns to achieve reduction of anxiety, depression, or other mental health struggles. Importantly, clients are encouraged to adapt and continue using CBT strategies to help maintain their well-being even after the therapy is finished. In CBT, structure is important both within therapy sessions as well as during the days between in the form of homework assignments. A typical session of CBT involves completing an objective questionnaire to assess the client's mood, setting an agenda to determine what issues will be discussed, review of prior session, joint problem-solving and discussion of agenda topics, followed by a review of how the session went. CBT ranges from as few as 6 weekly appointments up to 20 depending on need, with follow up booster sessions after the course of therapy is complete. CBT has been found to be effective with many presenting problems, and it is especially well-suited (and researched backed) for anxiety disorders, somatoform disorders (psychological problems manifesting in physical symptoms), bulimia, anger problems, and general stress (Hofmann et al., 2012). If you are looking for quick symptom reduction, coping skill development, and a straightforward, structured therapy approach, CBT is an excellent option for your treatment. If you like the principles of CBT but also want a deeper, insight-oriented approach, keep an eye out for clinicians who integrate CBT with other forms of therapy, such as psychodynamic, interpersonal, and existential. CBT is quite user-friendly; if you are experiencing more mild to moderate symptoms or can't access a CBT therapist, you can find a number of self-help books based in CBT principles that may offer you some relief (see resource list). What are your thoughts about CBT? Share any questions or comments below! Some other resources to learn more about CBT: More About CBT Socratic Questioning in CBT Self-Help CBT Book List Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 |

AuthorDr. Bethany Detwiler is a psychologist practicing in Allentown, PA. She specializes in mood and relationship struggles. She also is an adjunct professor of counseling at Lehigh University. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|