|

I spend a lot of time with suffering.

To provide psychotherapy is to sit with people who are often in the midst of a great deal of suffering, joining them in the space of their pain, helping them hold it, make meaning from it, and take action on that meaning. Thousands of hours of witnessing and sharing in the pain of others has brought to light some truths about what it is to be human, specifically around the universality of suffering. I have found myself turning to Buddhist ideologies, as well as philosophical theories and even the world of endurance athletics, to try to find the words to express more accurately how suffering has presented itself in my work and my own humanness. One of the core pieces of Buddhism which speaks deeply to our humanity is the concept of dukkha. Dukkha is often loosely translated as “suffering” or “unpleasant.” However, dukkha refers to suffering beyond the physical or even mental pain we tend to consider. It also encompasses disappointment with the loss that comes with change, the dissatisfaction inherent in the impermanence of the things that bring us joy, and suffering from the existential realities of aging, illness, and death. Dukkha sits at the heart of Buddhism’s four noble truths, with the truths presenting a path toward understanding dukkha, its causes, movement away from its causes, and then effort toward an enlightened state. (For more, check out this article). For our purposes, I emphasize here its recognition as a universal element of humanness. No person lives a life devoid of suffering, whether it is physical, mental, or existential. When we enter the world in our physical bodies, they come already equipped with dukkha as a guaranteed aspect of our existence. To live is to suffer. Universal suffering as a concept can sit heavy. It is unpleasant to suffer, and as a result, we often become preoccupied with not feeling our own pain. We all develop protective parts of us whose sole purpose is to numb, mute, or distract us from discomfort. You may notice internal managers who step in during times of possible stress, such as a tightly wound perfectionistic part of you looking to avoid suffering from making mistakes or disappointing others, or a part who keeps you tense and self-conscious in social situations to try to avoid suffering from judgment or rejection. You may also notice internal firefighters who douse the flames of suffering with alcohol or drugs, distract with compulsive behaviors or a short attention span, or even the ultimate escapist firefighters with thoughts of self-harm. These parts of us can become so strong that we are consumed with avoiding pain, at the cost of living a life that is present, grounded, and open to fully experience our humanness. In fact, living a life oriented to avoid our innate dukkha is to also place limits on our ability to experience the depths of joy, beauty, and connection. How do we move forward toward fulfilling lives while also enduring human suffering? Things here quickly become complex and deeply personal. Those who practice Buddhism strive to rid themselves of attachments, understanding fully the impermanence, transience, and unreal-ness of all existing things, so that there is no room for suffering when there are no attachments. Fully achieving this state of understanding is enlightenment, or self-actualization. Those who practice other religions also often use those belief systems to hold their suffering with humility and meaning. Personal values can also inform how we understand our innate suffering; values provide direction and purpose, which can offset our struggles and maintain guardrails on our individual paths. Endurance athletics introduces a scientific lens of how we suffer, and what we do with that suffering. A fascinating line of research has shown that endurance athletes feel less pain than the average person. A key study had participants hold their hands in ice water for as long as possible, and it was found that ultra-endurance runners experienced pain significantly less than non-endurance athlete participants. Non-athletes averaged 96 seconds in the water and rated their pain at the top of the scale; however, the endurance athletes withstood the ice water all the way up until the three-minute safety cutoff, and they rated their pain at an average of just six out of ten. How is it, then, that endurance athletes don't seem to feel pain like others do? The article plays with some different theories, with most of them pointing to psychological adaptation to the experience of pain and suffering. The theory that strikes me the most is that endurance athletes practice suffering as part of their daily training. Through repetition of feeling pain and moving through that pain, they recalibrate their psychological understanding not only of pain, but also of the limits of what they can tolerate. It is a common experience with exercise that our minds tell us that we can handle far less than what our bodies truly can handle. Through frequent exposure to suffering, these athletes have a sharpened understanding of their own grit and the limits of their tolerance. Let's imagine that we can build up our own grit to handle more general forms of human suffering, or dukkha. While we won't necessarily build grit that through running ultra-marathons or climbing mountains, perhaps we can in other ways. Rather than indulging in the parts of us that want to avoid suffering, what would happen if we were able to sit in our pain, welcoming it as part of our humanness? What if we gently asked our protective internal managers and firefighters to take a step back and give us a chance to actually feel our sorrow, disappointment, pain, and loss, to recalibrate our sense of what we can truly handle? Perhaps increasing our tolerance for suffering would help us not turn so readily to these parts that distract, make us anxious, or encourage us towards substances or risky behaviors; rather, we could have more permission to be our most authentic selves as we move through our lives, open to and accepting of the full range of the human experience. These shifts in coping techniques, however, should not be done without a system of support around us. Bolstering our sense of connection through sharing our pain with others gives us the foundation from which we can begin to hold our suffering with an open heart. The universality of suffering does mean that we will all experience our own individual pain; however, this universality also gives us a common thread among all people, as well as a common language we all speak. Sharing our pain with trusted family, friends, support groups, therapists, and others reminds us that we don’t have to endure suffering in solitude - in fact, our burdens often feel lighter when we aren’t carrying them alone. Working towards comfort with the vulnerability inherent in sharing, and on the receiver’s side, working on listening without judgment, abstaining from jumping to advice-giving, and showing empathy and compassion, can yield great comfort in the midst of human suffering. We can find this connection in any human relationship with people we trust, and it is the bread and butter of effective therapy. Healing doesn’t happen without connection and empathy as the foundation of the therapeutic relationship. I am working to embrace my ongoing relationship with suffering - in my personal life, the lives of my loved ones, and of course, the lives of my clients. Witnessing the bravery of people willing to sit in their pain and allow me to hold it with them is an incredible honor. It is these moments where I feel most human - when the universal language of pain is laid bare and felt together.

0 Comments

As the days get darker, colder, and shorter, it is a common phenomenon to experience the winter blues, or its more severe form, Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). What exactly does it mean to feel the winter blues or experience SAD? Symptoms of the winter blues can include the following:

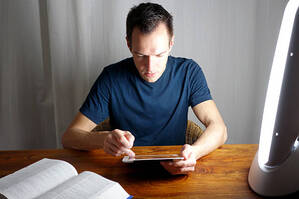

Thankfully, there is a tool to use at home to help stave off or manage the effects of the winter blues or SAD: full-spectrum light therapy. This treatment has been found to be highly effective and with minimal side effects, and it is affordable and easy to use. You can purchase a full-spectrum light box for personal use online for under $30-$100, depending on the model and technological features. The light is most effective at a level of 10,000 lux bright-white fluorescence (with harmful UV rays filtered out), which is significantly brighter than typical lighting. Light exposure should take place first thing in the morning, within an hour of waking up, and for 20-60 minutes per day during the months of the year when daylight is diminished. The light should be close to the face (16-24 inches away), but the user need not stare directly into it for the effect. Light therapy should be completed every day, even on weekends, and at a consistent time for optimal effects. It often can take some time of regular use to feel the effects of it, so it requires a consistent routine. Light therapy can become a foundation for a morning self-care practice of taking some time for yourself in the mornings before getting started with your day. You can have it by you as you have breakfast, check the news, knit, catch up on emails, or however else you like to start your day - just be sure to use it within an hour of waking up to not interrupt your sleep schedule. I am not affiliated with any brands or marketing, but I can personally attest to Verilux for quality light therapy products. Light therapy should be used with caution with certain medications or mental health diagnoses - always check with your medical providers and read manufacturer guidelines before starting any type of treatment. Some people may benefit more fully by using light therapy in conjunction with other treatments for SAD or depression, so it is important to explore all options for the care you need. To read more about light therapy, check out this overview from the Mayo Clinic. Have you considered, or have you tried light therapy yourself? Share your experience below.  I recently completed training in Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, and it has already been a game-changer for my clients and many others struggling with trauma, anxiety, depression, and more. However, EMDR is a therapy that often seems mysterious or even confusing. Even as a psychologist, before I received specific training, I had very little understanding of what EMDR was, how it worked, and what it was like to experience it . This post will shed light on what EMDR is all about and how it could help you or someone you know work through trauma, depression, anxiety, and many other struggles. I also provide some resources to find your own EMDR therapist. How emdr came to beOne fine spring day in the late 1980s, Dr. Francine Shapiro was walking on a sidewalk and thinking intensely about something that was really bothering her. Her mind kept perseverating on it, and she felt strong negative feelings as she focused on it. Oddly, a few moments of walking later, she suddenly realized her negative feelings had vanished and her thoughts had shifted, without any conscious effort on her part. Bewildered, she paused and considered what she had been doing while she was focusing on the distressing situation. In addition to walking, she had also been moving her eyes side to side while focusing on her distress. She became immediately curious about how the side-to-side movement of her eyes (as well as her feet) may have impacted her emotional and cognitive process. Shapiro's discovery led to series of first informal and then formal clinical trials evaluating the effects of bilateral stimulation (BLS), which is the intentional, repetitive, back-and-forth stimulation of the left and right hemispheres of the brain, on distress. More and more studies, which originally focused primarily on the veteran population with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), began to suggest a powerful effect of eye movement BLS on the reduction of PTSD symptoms. From those findings, EMDR was born. Since those early years, EMDR has been found to be effective for a vast range of presenting issues, including:

What it's like to experience emdrEMDR treatment includes a series of stages, and despite being a fairly structured treatment, there are many ways it can vary client-to-client, so this is a very general overview. Before beginning, your clinician should explain EMDR to you in detail, answer any questions you have, and obtain your consent to move forward. Then, the first stage focuses on treatment planning. During this process, your clinician will explore with you what you hope to achieve by completing EMDR. I think of the planning like a funnel - starting with broad areas of concern, and then honing in on a more specific problem along with the core belief you hold about yourself related to the issues at hand. When we start to explore what negative beliefs (e.g., "I am incompetent") underpin the more surface-level symptoms (e.g., performance anxiety), the target for EMDR becomes evident. Once the negative belief is identified, your clinician will help you determine what positive belief you'd like to strive towards that counteracts the negative belief (e.g., "I am competent, regardless"). The last step of the planning process is to then identify specific incidents in the past, more recent present, and/or future, where the negative belief felt especially true to you. This creates an incident map of your negative belief, which will guide the EMDR focus. You typically then select a single incident from the map to focus on first during EMDR processing. The second stage of EMDR is focused on resourcing. During this stage, your clinician works with you to build up your abilities to cope with and handle strong emotions or triggering memories. EMDR does have the potential to evoke intense emotions, so it is important that you have grounding and soothing skills to help you regulate your emotions if needed. These skills are also valuable outside of the context of EMDR, and can be used during any stressful moment. One of my personal favorites is helping clients develop a peaceful inner place. We use visualization and slow BLS to develop a vivid scene of a place, real or imagined, that produces a sense of tranquility. The third stage of EMDR is focused on desensitization and reprocessing. Once the plan and resourcing techniques are set, it is time to begin the application of BLS to work on the incidents and negative beliefs that have been identified. The clinician first takes you through a structured set of questions designed to activate the chosen incident (i.e., turn on your emotional response). Then, the clinician will instruct you to focus on the incident, belief, and associated feelings and sensations, and will apply a set of BLS for typically 20-45 seconds. There are many options for how the BLS can be applied - your clinician will review options with you and together determine the right choice:

The clinician will take you through 20-45 second sets of BLS. Between each set, they will check in with you, often asking, "what did you notice?". There are no "shoulds" or "supposed to's" with what you experience. The goal is to allow your brain, body, and mind to go where it needs to go during the set. The metaphor I tend to use is thinking about EMDR as driving down a highway, except you get off at each exit to check in before resuming your drive. Depending on the scope of the EMDR you agreed on with your clinician, as well as the emotionality and complexity of the focus, this stage may take a single session up to weeks or months to fully process through. Your clinician will be actively tracking what you notice between sets to gain a picture of the healing process. It is common for clients to first feel their distress more acutely in the earlier sets, as their brains take them into the unhealed memory. However, as the sets progress, clients very often start to notice subtle changes indicating that healing is taking place. This is where your clinician's training and clinician intuition will come into place to guide the process. After it seems the unhealed trauma, negative believe, or incident has been fully addressed, the clinician will then instruct you on installing the new positive belief you had come up with together. Focusing on the positive belief along with BLS helps to deeply instill a new framework for seeing yourself in a more compassionate light. Once the positive belief is installed, either EMDR is complete, or it is time to move to another incident or negative belief system and start again. After sessions, it is common to experience some residual effects of doing EMDR. These effects can vary greatly and may depend on what was addressed in the session, how activating it was, and whether it was resolved. Some clients report feeling more relaxed and present, better OR worse sleep, changes in dreams, body sensations, or in behavior (e.g., suddenly acting more assertive with others). Your clinician will check in with you about anything you may have experienced between sessions. Once an area of concern is fully processed with EMDR, you should feel a notable shift in your emotional reaction to the incident that was addressed, in that you still remember it, but you don't feel distressing feelings or hold the same negative beliefs related to it. Why we think emdr worksI say think for a reason. Like most forms of therapy, we aren't exactly sure of the specific mechanism of why it helps people feel better. EMDR certainly stands out this way, because it can sometimes feel like magic when a client's strong negative feelings seem to evaporate into thin air. However, there are several compelling theories about why we believe it has such efficacy, and I'll share two of them here:

Finding an emdr providerIf you are wanting to try EMDR for yourself, there are a few places to look to find yourself a trained provider. Because EMDR is a specific form of treatment and often used for traumatic memories, it is important to ensure that your clinician is properly trained in the approach. Here are a few places to begin your search:

References for more information

I hope this post was helpful in demystifying what EMDR therapy is all about. Feel free to submit any questions or comments below, or contact me directly if you'd like to learn more.

It's been a wild ride these last few months as the threat and then reality of the COVID-19 pandemic has hit full force. Here in Pennsylvania, we were notified only yesterday about a state-wide shut down of all non-essential businesses, which many others have been facing for far longer and with even more restrictions. As the situation unfolds, we are each faced with some hard choices to make as our worlds shrink smaller and smaller. Taking a proactive and intentional approach to social distancing and quarantine will be instrumental in finding peace and comfort in an uncomfortable situation. Following are some strategies to keep in mind to practice good self-care and promote emotional well-being during this challenging time:

I was recently talking with students in my introduction to counseling graduate class about one of the most unique aspects of learning to be a helper: being your own tool. As a therapist, my "me" is unmistakably present in every moment of the work I do. While my efforts are grounded in science and theory, they are undoubtedly woven together with who I am in the room: which thoughts, emotions, and personal memories come up for me while listening to my clients' narratives, how attentive and present I feel each moment of the session, and how I choose to respond or intervene. The beautiful thing about being my own tool is that I have the honor of lifelong learning and personal growth through this work as I support my clients in their own journeys toward healing. Following are some of the most poignant lessons providing therapy has taught me about myself...so far.

A few months back, I received an email from Lehigh (my PhD program and where I currently work as an adjunct professor) asking if I would be interested in teaching an eight-day course on group counseling for master's students in Kuwait. I paused and took account of my reactions to this question. Isn't it dangerous there? Would I feel uncomfortable as a foreign woman in the Middle East, alone? How would I connect with students from such a different culture, and within a society that has very different views on mental health? My stomach was performing anxious somersaults imagining this experience. However, I also noted a familial tingle of excitement - a different part of me was reawakening - the part of me that loves a challenge, embraces having my comfort zone stretched, and thirsts for experiencing something new and different, especially related to culture and travel. After a week of pondering, I made the decision to go. I am currently on my fifth day here in Kuwait. I am curled up on a couch in the lobby of my hotel, sunlight and warmth streaming in from the big windows overlooking the city. I am feeling utterly fulfilled and refreshed as a professor of these brilliant, brave, and complex students. I am also feeling enriched and enamored with this country, the beauty of Kuwait City, and the vibrancy of the culture around me. I felt some culture shock when I first arrived here. Kuwait does not have a big focus on tourism - and it shows. The airport had minimal signage for people new to Kuwait. The public transportation system is also limited and difficult to grasp if you don't speak Arabic. There is no hop-on-hop-off bus or tourism offices to plan your visit. Thankfully, I had some help with a meet and greet service at the airport to help me get my visa sorted and to transport me to my hotel. Lehigh also made sure I had contacts both at home and here in Kuwait to make sure things ran smoothly. Upon arrival, I was immediately struck by how urban it is here - the city is packed with tall apartment buildings, endless high-end shopping malls, busy roadways, and enough honking to rival NYC. The buildings are varying shades of sandy beiges and browns, bedecked with the visages of the Emir, smiling and waving. While the city is, in theory, walkable, it is not always pedestrian friendly, and crossing streets can be an extreme sport. On my second day, I got to meet two of my students who offered to take me out for coffee and dinner, and to show me around the city. While sipping on an iced matcha latte, I could already feel the warmth and generosity of the social climate. My students answered all of my questions about Kuwaiti culture, expressed curiosity about how it felt for me being here, and gave me great pointers on everything from how to cross streets without having my life flash before my eyes, to where to find top-notch knock-off perfumes at the Mubarakiya Souk (Arabic market). My class includes nine students who represent as vast an array of cultural, religious, and lingual backgrounds as Kuwait City overall. Some hold very traditional and deeply held religious beliefs; others embrace more liberal and modern attitudes. Mental health here is in its infancy - there is deeply held stigma about mental illness and treatment for mental health problems. And yet, my students are defying stigma and opening themselves to learning about a topic that is not widely embraced within their culture. That takes courage. A significant aspect of our course is having an hour long experiential group that takes place during each class meeting. Students rotate being group leaders, and student members are themselves - no role playing or acting. I led the first group, but since that initial meeting I have been a group member as well. As each meeting has occurred, I have been able to see my students learn how to let go of their anxiety about the unknowns of what will happen in group, embrace the beauty of organic conversation and connection, and dig deep to share parts of themselves that they tend to keep hidden. Due to their diverse identities, this means something different for each student - however each one has taken courageous steps to find and embrace those common threads that hold us all together. These common threads are woven through sharing laughter, speaking in our home languages and explaining cultural sayings, discussing cultural values that shape our experiences and perspectives, and holding together shared emotions of anxiety, sadness, isolation, joy, empowerment, and connection that reflect a universal language. We are creating a tapestry as a group that is intricately textured, patterned, and infinitely colorful. I am already mourning the impending end of this teaching experience as it is already halfway to completion. However, I remain excited about where this journey will continue to go, and what other common threads will emerge along the way. Until this past Sunday, it had been years since we took my stepdaughter bowling. The last time we bowled, I remember wondering how her tiny eight-year-old fingers would ever be able to lift that six-pound ball. Somehow, she hoisted the ball, dangling it haphazardly from her little arm, and staggered to the line, her whole body off balance. She would swing the heavy ball with the shortest of arcs, and it would drop almost straight down in front of her with an ear-splitting clatter. Then, we'd wait. About 35 years later, the ball would finish its achingly slow commute, zig-zagging from bumper to bumper and finally, finally, hitting a pin so gently that it would pretty much bounce off it. To her delight, she'd knock over at least a few pins every. single. time. She'd spin around with unbridled glee, jumping up and down. As the proud parents we are, we'd join her in her excitement, providing endless high fives and verbal affirmations of her bowling prowess.

Fast forward to present day, and we had a less-unbridled, ultra-cool 13-year old joining us for bowling this time. While excited for the family activity, she was more measured in her outward display. On the way to the ally, we warned her that this would be her first time bowling without bumpers. After a moment of pensive reflection, she simply said, "Okay, that's fine." My husband and I glanced at one another and then readied ourselves for the game. I marveled when she chose a 10-pound ball and lifted it with ease. She started off our first set. We gave her the usual pointers about keeping her wrist straight, taking her time, trying not to drop the ball straight down on the ally. She seemed determined and confident. The first bowl was a disaster. Her wrist twisted, resulting in the ball careening sharply into the gutter. Next bowl, an exact replica of the first, except into the gutter on the other side. Three rounds in and she had accumulated a total of six gutterballs and zero points. My husband and I started to waver. Was she not ready for regular bowling? Should we ask to switch to a bumper lane? It was so hard to watch her keep trying, and keep failing. Time for the fourth set. Miraculously, the ball stayed straight, and she knocked over several pins. We were all over the moon! She jumped up and down, a replica of her eight-year-old self, despite being such a cool teenager. As the day wore on, she got better and better scores, doubling her tally between the first and second games. She was proud, confident, and quickly reclaimed her former bowling prowess. So, what if we had moved to a bumper lane? Sure, she would've had much better bowling scores (and my husband and I would have, also, if we're being honest...). But she would not have learned. She would not have been challenged to focus on her skills - her wrist stability, knowing how to slow her pace, lining her feet up properly with the pins. She would not have realized that she can learn, grow, and see her abilities bloom right before her eyes through her own hard work. In short, she wouldn't have had an opportunity to believe in herself. Bowling without bumpers gives us a perfect metaphor for why we should find ways to embrace the adversity we face. Just as our kid didn't grow in her skills and confidence without first failing and struggling, we don't grow and learn without facing some hardship ourselves. If we were to have everything we want without working, or struggling, or failing first to get there, we wouldn't value the things we have or the skills we demonstrate. As parents, it is easy to want to clear out obstacles that impede our children, or rescue them when they fail. It hurts to see your kids suffer. But when we clear out hurdles in their path, they never have a chance to strengthen their own muscles and realize that they CAN do it. It might not be pretty, and they might throw a few gutterballs, but they will eventually succeed. And that knowledge is priceless. Unbelievably, the holiday season has returned again. It feels like just yesterday was back-to-school season, and here we are, up to our necks in turkey and mashed potatoes, shivering in the blustery cold weather. This time of year tends to be a mixed bag for many. It can bring joy, hope, and optimism through delicious meals, time spent with family, beautiful decor, and anticipation for happy memories. It can also bring an increase in stress, however, due to immense pressures of preparing food, hosting guests, traveling, navigating crowded roads and stores, spending money, and engaging with family who may not be your ideal companions. For others, it can be a time of profound loneliness and grief due to family estrangement or conflict, coping with the loss of a family member, or battling seasonal mood symptoms. For many, it can be a whirlwind mix of all of the above. Let's go over a few quick tips to help navigate this assortment of emotions and make the most of the holiday season.

What helps you get through the holiday season in one piece? Share your thoughts in the comments. Wishing you a joyful and mindful season! Anxiety disorders, which include everything from generalized anxiety, to social phobia (aka, social anxiety), to obsessive-compulsive disorders, are the most commonly diagnosed mental health problem in the US. In fact, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million US adults. More disheartening is that less than half of those with anxiety disorders receive help for their struggles. When I work with clients who have anxiety, I often discuss with them the cycling and self-reinforcing patterns that anxiety tends to induce. This three-part series will review common ways that we give in to, and therefore worsen, our anxiety. Part 3: Self-Medicate It Anxiety can be exhausting, grueling, and overwhelming. It consumes copious amounts of physical energy and mental space. Many clients describe their racing thoughts as a track running constantly in their minds at 100 miles per hour, taking up valuable room that could be used for more productive things. In Part 1, we discussed what anxiety is and the value of insight. In Part 2, we reviewed the negative effects of finding ways to avoid anxiety triggers, which only serves to make anxiety worse in the long-run. However, avoidance is only one of many less-than-helpful ways of coping with anxiety. The discomfort of anxiety offers tempting invitations to find quick fixes for relief. Those facing physical exhaustion from anxiety-induced sleep issues or fatigue may grab a few extra cups of coffee or a Red Bull to get through the day. Some who always feel keyed up or tense may look to alcohol or other drugs to take the edge off. Still others turn to what they can control and rely on - food, shopping, social media - to provide distraction or comfort. Let's break down some of these quick-fix anxiety responses that may not be so helpful for long-term symptom reduction:

Something to try: A saying I use often with clients is to strive to find your comfort within life's discomfort. We have no way to ensure life will be smooth and easy; in fact, it tends to be just the opposite - but that's what makes our lives meaningful. We are tasked with finding ways to cultivate a sense of peace even when our lives feel far from peaceful. When you are feeling anxious, practice closing your eyes, taking some measured breaths, and mentally stepping back so you can appraise your situation from a different perspective. Try to hold in your mind the realities of whatever discomfort is causing your distress, but also hold your grit - your inner strength and resilience - and remind yourself that you can lean into the discomfort with grace and persevere. Breathe through the discomfort and notice how even in the midst of our tumultuous worlds, we can still hold peace within. I hope you enjoyed this three-part series on anxiety! Are there other topics you'd like to learn more about? Share them below or reach out. Anxiety disorders, which include everything from generalized anxiety, to social phobia (aka, social anxiety), to obsessive-compulsive disorders, are the most commonly diagnosed mental health problem in the US. In fact, according to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, anxiety disorders affect 40 million US adults. More disheartening is that less than half of those with anxiety disorders receive help for their struggles. When I work with clients who have anxiety, I often discuss with them the cycling and self-reinforcing patterns that anxiety tends to induce. This three-part series will review common ways that we give in to, and therefore worsen, our anxiety Part 2: Give Into It By far the most common anxiety mistake I see people making is giving into it. As I reviewed in Part 1, anxiety often boils down to a misapplied fight-or-flight response to a threat that isn't truly life-or-death. It is a good thing that we have fight-or-flight, as it keeps us from harm through readying our minds and bodies for action or escape. However, sometimes that response can get linked up with things we face in life that are not actually threatening enough to warrant such a strong neurobiological response (e.g., meeting new people, public speaking, spiders, unknowns, compulsive behaviors, being imperfect, etc.), resulting in a state of anxiety. When we are in an anxious state, our minds and bodies are basically screaming at us to get ourselves OUT of that situation through trying to find things to control (hello, perfectionism!), numb the anxious feeling (hey there, comfort food), or avoid the threat altogether. This post focuses on the danger of avoiding the anxious trigger. What happens when we listen to our screaming brain and simply avoid the trigger? Avoidance often gives us immediate relief from anxiety, but it does us no favors in terms of making our anxiety better. In fact, it seems to make it worse. By giving in and avoiding the trigger, we reinforce our brains, telling ourselves that yes, this threat I am facing truly is life-or-death, and we give our fight-or-flight response a pat on the head (brain?) for a job well done. The next time we face the same trigger, our brains will respond as actively, if not even more so, as the first time we faced it because we reinforced the fear by giving in. So what should we do instead? Face the fear directly. Anxiety lives on a bell curve (see below) - it builds up with those initial signs (the red zone) and continues to grow in intensity (the orange). Often, we look for ways to cut those anxious feelings before it crests - we become afraid of our own anxiety - through avoidance, numbing, or control. However, if we can muster our inner strength to sit in the discomfort of anxiety, it will subside. The acute anxiety state does not last forever, and the more that we face the threat, breathe, and ride the wave, the less intense our response will get every time we face our fear. I experienced success with facing fear head on when it came to public speaking. Back in high school and college, I would be an absolute mess when I had to present a speech in front of my class. Shaking hands, quivering voice, cold sweat, that gripping, hollow feeling in my stomach like when you miss the last step on a staircase - all that good stuff. However, I kept pushing myself to face, acknowledge, and ride out those anxious feelings every single time. Over the years my discomfort became more manageable, and I have since completed some pretty big milestones, including conference presentations, my dissertation defense, and currently teaching graduate students for the sixth semester in a row. I still get butterflies, but my fight-or-flight response is far more subdued and manageable - and I fully attribute it to facing my public speaking fear and telling my brain over and over, "This makes me feel some stress, but I know I will be okay. Let's channel these nerves into excitement and get on with it."

Something to Practice: Identify a trigger for your anxiety response. Sticking with my anecdote above, we will use public speaking for an example.Then, think about a step towards conquering that fear. The first step should be anxiety-provoking enough -- but not overwhelmingly so. For example, one step towards conquering public speaking fear might be raising your hand in class. Then, schedule 3-5 times this week to practice facing that initial step without avoiding it. Keep track of your anxiety symptoms before, during, and after - and notice how they will decrease in intensity with repeated exposure. Once you get to the point where raising your hand no longer elicits substantial anxiety, move to the next step, such as attending a networking event or job fair, or taking a lead role for a class presentation. Work your way systematically through these steps and watch the anxiety drop. Extra resources: More about fear exposure for social anxiety Treating phobias with fear hierarchies More on anxiety and fight-or-flight Have you been able to conquer any of your fears? Share your success stories in the comments! |

AuthorDr. Bethany Detwiler is a psychologist practicing in Allentown, PA. She specializes in mood and relationship struggles. She also is an adjunct professor of counseling at Lehigh University. Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|